Five minutes to midnight

The End Is Always Nigh

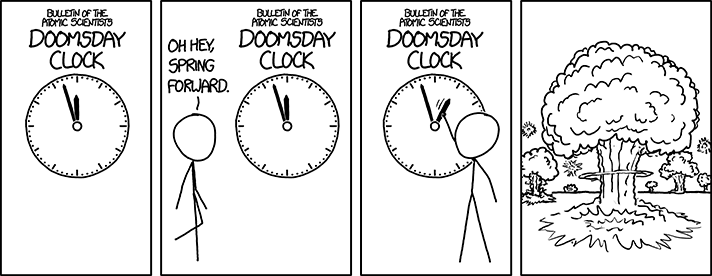

I suspect I am not the only person to feel this way, but for me the present moment seems to have a strong five minutes to midnight character to it. Another way of putting it is the end is nigh, although I prefer five minutes to midnight because it carries fewer religious connotations. (And also because it gives a nod to the famous Doomsday Clock started by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.)

|

| From xkcd.com |

First and foremost in my mind is the climate crisis. We're told by the IPCC the tipping point could be as low as 1.5°C, which is only 0.4°C away from where we are now. And that (making optimistic assumptions) we have a CO2 budget equivalent to 10 years of emissions at today's rates. Beyond the tipping point the future looks so bleak that even if humans do survive it's hard to see there being very many of them, or their lives being very nice.

But it isn't just the climate crisis: Kim Jong-Uns new nukes; Putin's brinkmanship; dawn of AI; the spread of impossible-to-regulate gene editing; the list goes on.... It's hard to imagine that one of these isn't going to finish us off in the near future, which makes five minutes to midnight seem fairly apt.

So it would seem we've had exceptionally bad luck to be born in the last moments of human history. (Although, an optimist might point out that this generation of humans has suffered less than any before it.) However, I'm going to propose a theory that there's actually nothing exceptional at all about the experience we are sharing in this moment. My thesis is that the vast majority of experienced moments share the same five minutes to midnight character!

But how is it possible that the majority of experiences share this character when the five minutes is supposed to represent just one $24^{th}$ of all human history? I'm going to present two arguments which are very different in nature. These are not alternative hypotheses, they are independent arguments which might both be true. Which means is that if you don't buy one of them, the other might suffice!

Argument 1: Intelligence and exponential growth go hand in hand

There are only two types of variable exhibiting approximately exponential growth

- A purely abstract variable unrelated to anything physically meaningful. For example the Fibonacci number $F = F(n)$.

- A variable which only appears to show exponential growth because you haven't looked far enough into the future.

|

| From https://www.flickr.com/photos/mplemmon/3203403780 |

A lot of statisticians - such as the late Hans Rosling - argue that human population is already levelling out and is predicted to settle at between 10 and 11 billion. However, this doesn't mean we're moving towards a sustainable future since the - already unsustainable - rate at which we are extracting our planet's resources is still growing exponentially. So don't write off collapse just yet!

My argument is that exponential growth of some form (be it in population or resource depletion) goes hand in hand with intelligent life. This is because life arises out of a fight to survive and an intelligent species is one that has mastered that fight and therefore grows exponentially (and unsustainably). You may argue that if it was truly intelligent it would rein in it's rapacious instincts, but that would be to conflate the intelligence of the individuals with the intelligence of the group.

In Our Final Century, astronomer royal Sir Martin Rees makes an interesting observation. If you are told that a tombola contains tickets numbered $1$ to $n$ but you have no idea what $n$ is, and you are only allowed to pull out one ticket, your statistically-best bet for $n$ is twice the number on the ticket you pulled out. Similarly, if you are asked to guess how many humans will ever live and you are told only how many there have ever been (around 100 billion) then - in the absence of any other information - the best guess is twice that number (around 200 billion). If the population were to continue to grow exponentially we'd reach that number very soon. Even if it levels out at 10 billion, that still only gives us about 1000 years. And that ignores the fact that the exponential growth has just shifted from population to resource exploitation, so we're probably still five minutes from midnight.

One of the risks highlighted by Sir Martin Rees in his book Our Final Century is artificial intelligence. The idea is that someone sets a super intelligent AI a really stupid goal, like: make as many paper clips as you can. Off it goes converting every resource it finds into either paper clips, or identical copies of itself, and eventually all organic life on Earth is snuffed out as Earth is covered by paper clips and paper clip making bots. This is known as the grey goo scenario.

If, (and it's a big "if"), sufficiently clever AI is created before we wipe ourselves out, then it's only a matter of time before someone does this. But notice that the AI bots will follow the exact same trajectory as their human ancestors: their intelligence will go hand in hand with exponential growth. So, even if we consider the goo that replaces us to be capable of experience, it will still be true that the majority of experienced moments have a five minutes to midnight character.

Argument 2: Self aware existence is unstable and only the multiverse makes it seem otherwise

|

| Credit: me |

This argument takes the multiverse as a given. The multiverse is what you get if you take the Schroedinger equation literally and apply it to the whole of reality rather than arbitrarily deciding it only applies in some small arena. It's wrong to think of it as parallel universes which evolve independently of each other. Some physicists - including Hugh Everett III the founder of the theory - describe it as a continuous branching of reality as time marches forwards. I prefer to think of it as a collection of timeless moments, each of which contains embedded historical records which suggest a path through the space of all possible moments. However, the space itself contains no privileged path corresponding to a single true history.

In his book Our Mathematical Universe Max Tegmark suggests an experiment that you can perform to prove the existence of the multiverse. It's very simple: set up a gun to fire a bullet once per second; build up sufficient courage; then stick your head in the firing line. Clearly most near-future-like moments involve a dead you, but there will be some where you survive because, say, the gun's mechanism becomes stuck. That means that there are some futures where you are alive and shouting "eureka - I've proved the multiverse exists". You don't need to worry about the other futures because you won't be in them.

Tegmark goes further and suggests you could repeat the experiment over and over again. Each time something even more freakish should occur to somehow save your life. A meteorite falls out of the sky and knocks the gun out of action, say. Anyway, please don't try this - not because I don't expect it to work from your point of view, but because it won't work from my point of view. (Usually.)

This experiment might seem ridiculous but it's just possible we've all been performing a similar one for the past 70 years. Look at the list of nuclear close calls and it seems like we've been incredibly lucky as a species to have survived so long after the invention of the bomb. Perhaps we haven't been lucky it's just that there are more people looking back from moments in which global thermonuclear war didn't happen than from moments in which it did, even though there are more moments of the latter type.

In 1948, after the Americans had developed the A-bomb but before the Soviets caught up, Bertrand Russell argued that the United States should strike pre-emptively. He understood game theory and believed it showed the situation would become highly unstable as soon as two nations had the bomb, making an all out war inevitable. So it made sense to get it over and done with while our side still had the advantage. Eventually the USSR got the bomb, all out war did not break out, and Russell decided he was wrong and became a founder of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). But it's just possible that he was in fact right the first time round, that in most of the multiverse his worst fears were realised and full scale nuclear war was triggered as soon as both parties became nuclear armed.

We can go even further and claim that the reality we live in is inherently unstable. We are all five minutes from midnight. In the multiverse as a whole, most people alive in 1962 died in 1962 when the USA and the USSR fired their entire arsenal at each other. Most of us alive in 1983 died in 1983 when the deployment of Pershing II missiles in Germany led to a nuclear holocaust. Perhaps, it's just the small number of us who live on those sparse branches where that did not happen who are looking back and thinking: that was close.

Perhaps the multiverse is the real-world Infinite Improbability Drive. It makes the impossible happen - every conscious being at every moment in history is facing imminent and almost certain death yet looking backwards we see that we, as individuals and as a species, miraculously escaped every similar situation in the past.

Comments

Post a Comment